Ever watch a Grand Prix and wonder how the teams, cars and drivers get from event to event? The logistics of moving the Formula 1 circus between destinations is akin to a military operation. We take a look at the fascinating logistics of Formula 1 and how one of the world’s largest sporting events moves between countries on time.

All images © F1Destinations

Before the chequered flag has fallen on Sunday’s Grand Prix, the pack-up operation is already underway to move F1 onto its next location. Some spare parts, such as engines can be packed up ready for transit as early as Saturday, as there’s not enough time to change an engine between the end of parc-ferme and the start of the Grand Prix.

The wider tear-down plan is intricately set out on the Thursday morning before each race weekend begins. It’s not uncommon for circuits to be completely cleared of F1’s presence in as little as eight hours after the Grand Prix ends.

If two races are separated by two weeks, there’s a window of ten days for travel and transit. If it’s a back-to-back race weekend, the time available to get everything operational at the next venue between back-to-back races is just three days. Double headers which involve road travel across Europe can be some of the tightest turnarounds of the year.

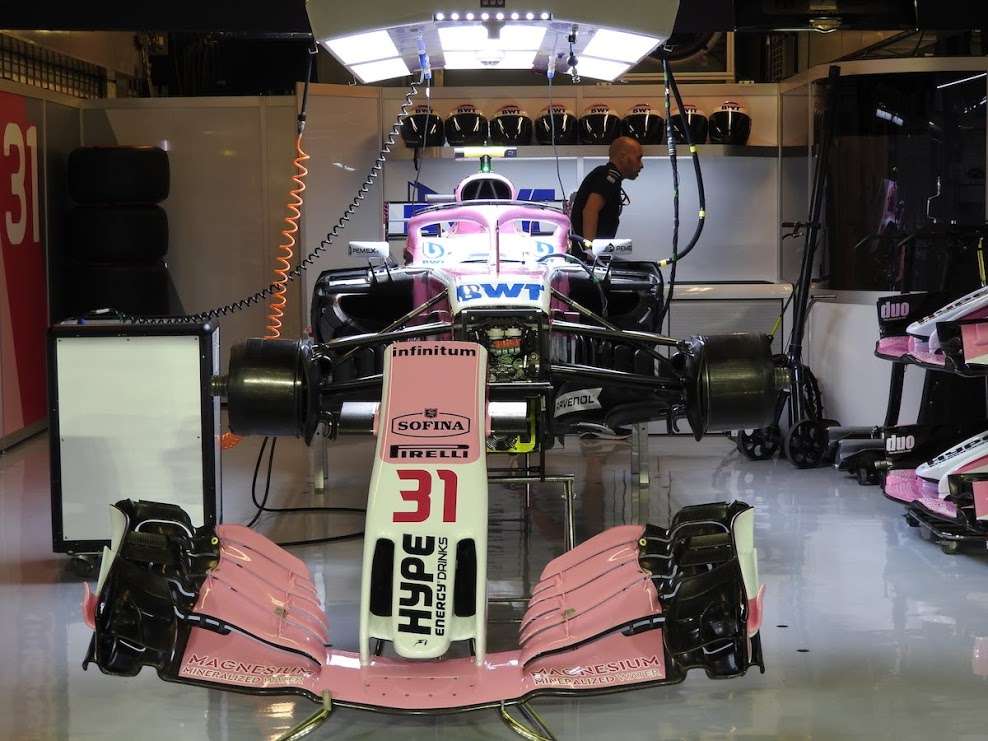

Almost every member of each Formula 1 team has their own role in helping with packing up the garages. The garage walls are de-constructed, and computer racks – and the miles of cabling that go with them – are packed away. Engines and tyres are usually returned to their manufacturers and the cars themselves have to be dismantled, but this can only be done after the FIA have finished their inspections to check each car’s legality.

For the European races between the Emilia Romagna and Italian Grands Prix, the majority of the teams’ equipment is transported by road to save money. That includes the team’s lavish motorhomes, which are dismantled by another team of people and then packed into trucks, before being then driven to the next event.

If it’s not a back-to-back race weekend, cars will be flown back to the teams’ factories to be repainted. Suspension and wiring is checked and replaced if needed and then the machinery is packed once again and driven to the airport.

Ferrari, AlphaTauri and Alfa Romeo’s cargo will meet at a mainland European airport, while the British teams’ goods arrive at the East Midlands airport. From there, the crates are handed over to DHL, F1’s official logistics partner, and are loaded onto cargo planes which are chartered by Formula One Management (FOM). The teams still have to pay for this service, though.

DHL: Formula 1’s official logistics partner

As Formula 1’s longest-standing partner, DHL have almost 40 of experience in the field, making the most of land, air and sea travel to ensure that every aspect of the world’s fastest sport, from team equipment, tyres and fuel, to hospitality and catering goods, is always delivered on time.

F1’s relationship with DHL is one of the most critical; without it, the show simply wouldn’t exist. The job done by DHL can be compared to that of the work carried out by an F1 team during a pit-stop; a mass of people coming together to ensure a job gets done as efficiently and safely as possible, choreographed to perfection.

DHL’s impressive statistics:

- DHL estimate that, on average, each team ships the equivalent weight of eight elephants per race.

- It’s also estimated that each team will transport around 50 tons of cargo per year, which can cost upward of $8 million.

- DHL cargo travels upwards of 130,000km over the course of a season, in up to six or seven Boeing 747 cargo planes per event.

- Up to 300 trucks head from race to race. If you put them all together, they’d make a convoy longer than 5km!

- Over a season, teams ship 660 tons of air freight and 500 tons of sea freight (the equivalent of 165 elephants, if that’s your preferred scale of measurement).

- The cargo crates are specially designed to effectively fill all the space available in DHL’s planes.

- There’s around 100 people involved in the logistics overall, including people from DHL, team personnel and locals to each event who aid the operation.

- Each team has around three pallets worth of priority cargo. This will be the first cargo that arrives at the circuit, allowing teams to begin setting up their cars and garages. It’s up to the teams what equipment goes in these pallets.

F1 logistics and overseas travel

Logistics become even more complicated for the Grands Prix held outside of Europe. The way in which everything is shipped depends on a variety of factors, including the distance between venues and the amount of time available.

To cut down on costs, some equipment is sent by sea. Teams begin shipping five lots of cargo out for the first five fly-away races of the season in January. Typically, the cargo will be sent on rotation around the world. For example, after the Australian Grand Prix has finished the sea freight will be sent to the sixth fly-away race of the year in Singapore and stored there until the Grand Prix weekend in September.

Back-to-back fly away races can be the most challenging logistically, as there are only three days to get goods between circuits which are thousands of kilometres apart. That, coupled with a changing time zone, makes it an extremely tight schedule!

The team will pack priority pallets for each Grand Prix, which include all the essentials to set the garages up, such as computers and garage walls. These arrive at the next circuit first, on the Tuesday after the last race. Customs checks are sometimes carried out at the circuits themselves rather than at the airports, in order to speed things up.

For both fairness and safety, the team’s crates are placed in the pit-lane of the venue and are not allowed to be accessed until every team’s cargo has arrived. Once this has all been set up, more cargo – including the cars themselves – will arrive on the Wednesday, with the same protocol taking place.

By Wednesday afternoon, everything in the pit lane and paddock is fully operational and ready for media day on Thursday.

And all of that, of course, is just the logistics of taking the trucks, motorhomes, cars and equipment from race to race. Factor in the large number of hotel rooms which need booking, hire cars which need to be found, food which needs buying, catering arrangements which need organising and internet connectivity which needs setting up and, all in all, the race before the race can be even more chaotic than the Grand Prix itself!

Trying situations: Formula 1 logistics at triple header events

A number of factors can make the logistical operation even more trying. Formula 1’s first ever triple header in 2018 proved a testing time, with three races on three consecutive weekends across Europe.

Some teams used alternate motorhomes for the middle weekend of the triple-header. For the 1,600km journey between the Red Bull Ring and Silverstone, each truck had three drivers to ensure the cargo never stopped moving aside from fuel stops.

Triple headers have since become an established part of the Formula 1 calendar and the teams and their logistical partners have adapted to ensure freight arrives on time – though delays nearly threw the final triple header of the 2021 season off course…

How the weather can interrupt Formula 1 logistics

Formula 1 teams and their logistical partners can plan transportation down to the minute – but sometimes those plans can be thwarted by factors outside of anyone’s control. The weather can cause headaches for everyone involved.

In 2021, Formula 1 staged its first triple header of flyaway races with the sport visiting Mexico, Brazil and Qatar on three successive weekends late on in the season. As the pack up was completed as usual at the Mexico City Grand Prix, fog caused six hours worth of delays in transporting three cargo planes of freight from Mexico City’s airport to Brazil.

The delays meant that some teams’ freight did not arrive in Sao Paulo until Thursday afternoon and with qualifying taking place on Friday – as this race used F1’s new Sprint format – this was a far from ideal situation.

The FIA subsequently waived the usual curfew and changed the scrutineering deadline, allowing teams extra time to prepare their cars for the race weekend. Their regular schedules rewritten, every team was able to complete their preparation in time for opening practice on Friday. F1’s Sporting Director Steve Nielsen says that Formula 1 and the teams would conduct a “full post-mortem” of the situation in order to work out what lessons could be learned.

This wasn’t the first time that weather had impacted preparation plans in Formula 1. The tight turnaround between the Mexican and United States Grands Prix in 2018 was also almost derailed by adverse weather conditions. A hurricane, which had made landfall in Florida, was to cause major delays to the transportation of Formula 1 freight.

The teams’ sea freight, which was headed to Mexico, was due to be delayed until the Thursday before the race – leaving too little time to set up. DHL had to think quickly and find a solution. They took the identical kit which had been used by the teams at the United States Grand Prix to Mexico and sent it by road, as is the norm for the European races, immediately after the Grand Prix, eliminating the need for sea freight. Quick thinking is essential to ensure that Formula 1 always arrives on time.

Formula 1 logistics: Racing through the pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic presented Formula 1 with unparalleled logistical issues. Not only was travelling between countries exceptionally difficult, keeping crew members safe and healthy would also prove to be a challenge. Strict testing regimes were put in place and interactions between teams was limited.

In 2020, DHL aided Formula 1 through 17 races, set at 14 venues, over 24 weeks in a season unlike any other. After the cancellation of the 2020 Austrian Grand Prix, the teams’ equipment was transported to four strategical hubs in the United Kingdom, Belgium, Canada and Vietnam, ensuring racing could resume at any venue globally with a ten day notice.

The 2020 Formula 1 season eventually began in early July with the 2020 Austrian Grand Prix. DHL transported over 40 containers by sea, along with 19 trucks by road, for the delayed F1 season to finally begin. Over the course of the first pandemic-impacted season, DHL transported 800 tonnes across the season by air, sea and road.

With travel restrictions in place, transporting freight became an increased challenge. Some concessions were made to ensure everything ran smoothly, including Formula 1 hosting its first ever two-day weekend at the 2020 Emilia Romagna Grand Prix – with the Imola race following just seven days after the Portuguese Grand Prix.

Formula 1 logistics and sustainability

In November 2019, Formula 1 set itself the objective of having net zero carbon emissions by 2030. While certain elements of achieving this include using 100% sustainable fuels in Formula 1 cars and simpler acts such as reducing single-use plastics in the paddock, one of F1’s biggest hurdles to overcome in achieving net zero status is within the realm of freight logistics.

Formula 1 provided an update in December 2022 on its progress in improving the sustainability of the sport. It noted that freight containers have recently been redesigned in order to be shipped in more fuel-efficient aircraft, while remote broadcasting has been implemented to lower the amount of travel freight.

The sport has set about planning for regionalised calendars in future seasons, grouping races together by geographical location thus lowering air miles and travelling distances. Grouping races together in this way may also allow for use of more efficient modes of transport – freight trains for example – to transport equipment between circuits.

During 2022, over the triple header of events which visited Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium, Zandvoort in the Netherlands and Monza in Italy, Mercedes trialled the use of biofuels for their freight. Impressively, their research found that the use of such fuels depleted their carbon emissions by a staggering 89%. Instead of using fossil fuels, the teams’ trucks were powered by Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO 100) biofuel.

The f1 logistics opperation is so fascinating it must be a dream job for some of the people associated with it

Interesting stuff i would have like to join your logistics team.

Hey this is Pravin kumar K from India i love F1 … I have completed my master of international business and i have decided to join with F1 career ..