Almost 75 years ago, the very first World Championship Formula 1 race took place at Silverstone. What was the 1950 British Grand Prix like for fans attending the event? We take a look through the official race programme and contemporary reports to find out.

The date is May 13, 1950. The location is Northamptonshire, England. More specifically, the location is Silverstone. Just three years earlier, the area was known as RAF Silverstone but, not long after the end of World War II, the former airfield had been converted into a racing circuit.

After hosting several national race meetings in 1948 and 1949, Silverstone was to play host to the Grand Prix d’Europe for the first time in 1950. An international race meeting, the 1950 Grand Prix d’Europe – or, nowadays, more commonly referred to as the 1950 British Grand Prix – was the inaugural round of the Drivers’ Championship in the first fully-fledged Formula 1 season; the first race of a new era for international motorsport.

The 1950 British Grand Prix Programme

By taking a look through the official race programme and looking at contemporary news reports, we can get some idea of what the experience was like for fans attending the race at Silverstone in 1950. The 1950 British Grand Prix ran over three days, from Thursday to Saturday, though the Saturday-focused programme suggests that practice sessions took place without the public in attendance.

Incidentally, the programme was priced at one shilling – around five pence by today’s standards, which is slightly less than the £25 which is currently charged for race programmes, and a lot less than the £100 at which copies of the 1950 guide occasionally appear at auctions in the present day.

As for race day tickets, those apparently cost just over seven shillings – or the equivalent of 38 pence. The average cost of 3-day tickets for the 2024 British Grand Prix is £545, according to our annual ticket price analysis.

The foreword of the programme declares that the race is “the greatest occasion in the history of motor racing in this Country”. Motorsport was still very much a minority sport in the 1950s but, almost 75 years later, Formula 1’s popularity continues to grow in front of a global audience. Though the race did not receive widespread media coverage in 1950, it’s easy to see with hindsight that the 1950 British Grand Prix was a significant milestone in the dawn of the modern era of motor racing.

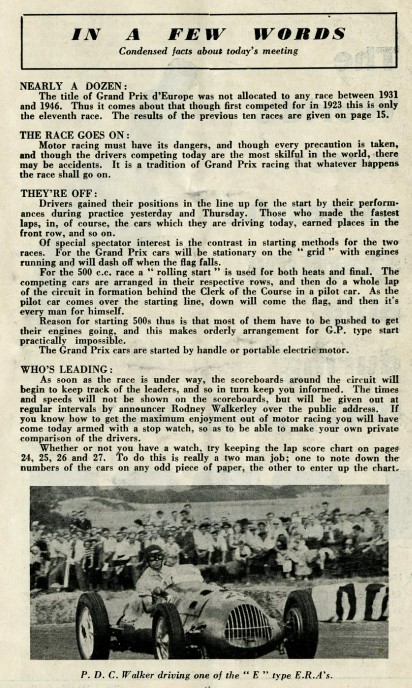

The race programme acts as a rudimentary guide for spectators, many of whom had probably never previously witnessed motorsport in person. It explains the different coloured flags used by marshals, the differences between rolling starts and standing starts, and tells spectators to expect overtaking cars to pass on the left-hand side of the road, as it was tradition to use the French rule-of-the-road.

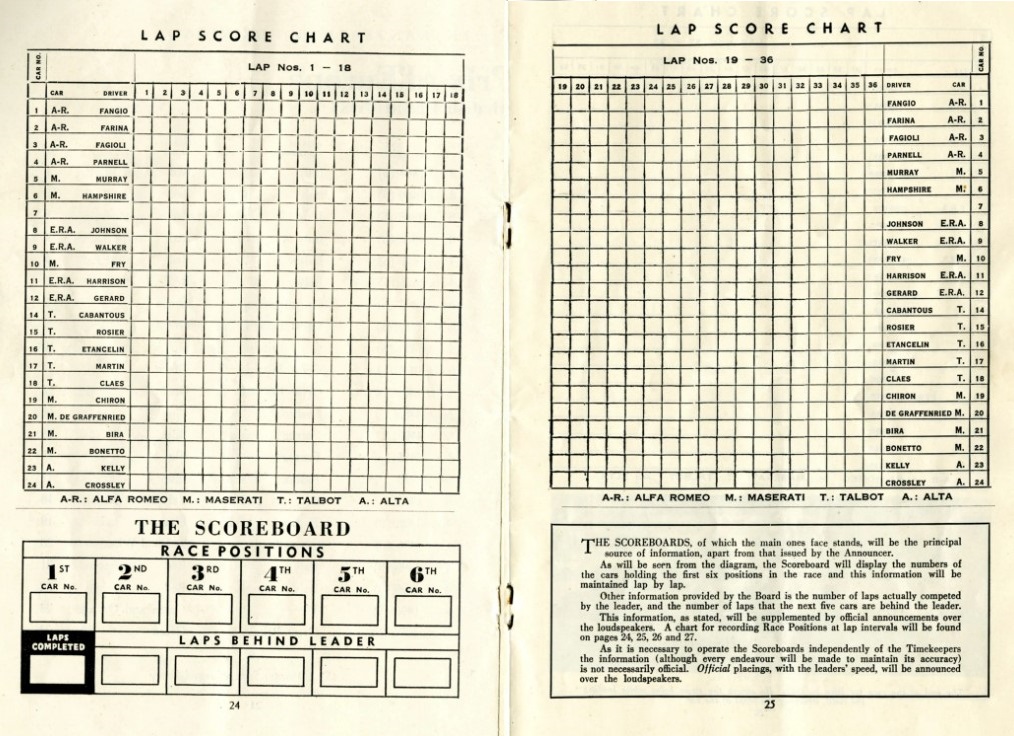

There’s also a guide on how to keep track of the race via the scoreboards located around the circuit, which suggests that spectators should have come “armed with a stop watch”, if they are to “get the maximum enjoyment” out of their day. Spectators were kept updated on drivers’ positions in the race via 125 loud speakers, which had been linked together by seven miles of wiring around the circuit.

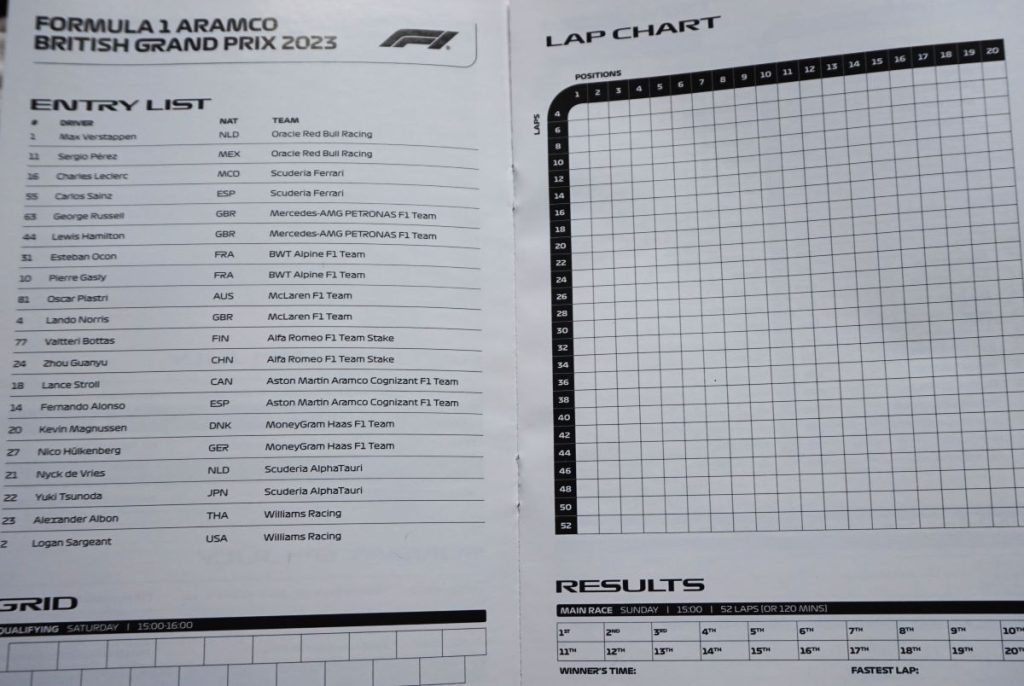

Within the pages of the programme is a “lap score chart”, allowing enthusiasts to mark down the position of each car on each lap. The lap charts have remained a feature of the British Grand Prix programme through to the present day.

In addition, a rundown of prize money is given, which shows that the winner of the 1950 British Grand Prix would be paid £500 for their troubles (around £15,000 in today’s money), with every driver who finished in the top ten positions receiving a monetary prize – plus an extra £30 for the driver who set the fastest lap.

Ferrari “Regretfully” Missing

Alfa Romeo dominated the early days of Formula 1 and the 1950 British Grand Prix was the first time that the team competed on British soil. The Alfa Romeo cars had arrived at Silverstone having been driven – illegally – on public roads from Banbury, around 20 miles west of the circuit.

The team filled all three podium positions at the conclusion of the race, with eventual inaugural World Champion Giuseppe Farina leading home fellow Italian Luigi Fagioli and British driver Reg Parnell, who secured the first home podium finish in F1. Parnell was invited to compete with Alfa Romeo as a result of being the British driver with the most Grand Prix experience.

The race also marked Juan Manuel Fangio’s first visit to England. Fangio was the favourite heading into the event, as he had won two of the four non-championship races which had been held in 1950 prior to the British race. He would ultimately retire from the Silverstone race after running wide at Stowe and hitting the straw bales.

A notable absence from the Silverstone race was Ferrari. It was said to be a “regretted absence” in the programme, given that the team was Alfa Romeo’s closest rival. The 1950 British Grand Prix, as a result, was not a particularly memorable on-track affair.

Ferrari had been expected to bring three cars to the race, along with an extra entry for “Britisher” Peter Whitehead – but the entries were cancelled, allegedly due to a dispute over starting money, with the decision made clearly in plenty of time before the programmes were sent to the printers.

Ferrari would instead make their World Championship debut at the next event, the 1950 Monaco Grand Prix and would seal their first F1 win at Silverstone one year later.

Support Races & Other Events

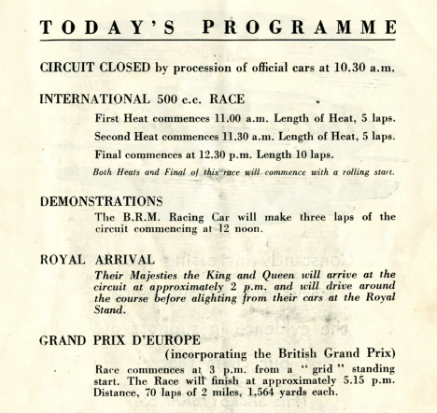

The on-track schedule is listed within the pages of the 1950 British Grand Prix programme. Unlike in the present day – with its nightly headline concerts, entertainment zones and other off-track attractions – there was little for fans to see aside from racing on-track.

The circuit was closed off at 10:30am by a parade of official cars before racing commenced at 11:00am. Before the Formula 1 action, there was an International 500cc support race – for which there were two 5 lap heats and a final race consisting of 10 laps. Among the entrants in the 500cc race was 20 year-old Stirling Moss, who would win the event.

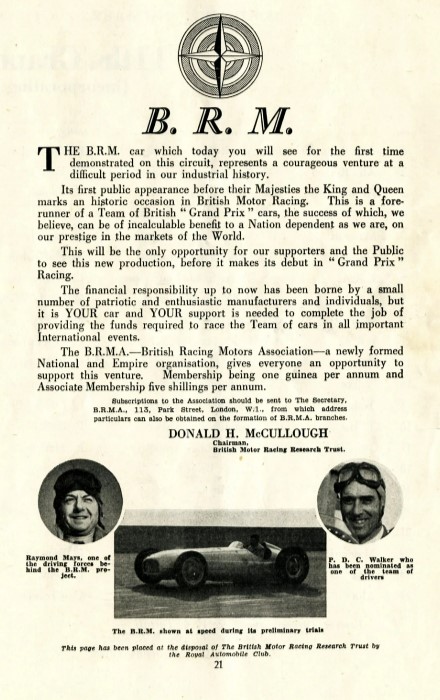

At noon, a demonstration lap took place by British team BRM, who had their own double page spread within the programme; including a call for monetary support for the project from fans – “it is YOUR car and YOUR support is needed to complete the job of providing the funds”. Membership was priced at “one guinea per annum”.

The team was to be a new hope for Britain in the international motor racing scene – and this was to be the car’s debut appearance, albeit not in a racing capacity. The P15 was driven on a demonstration lap by Raymond Mays.

The trust fund model used by BRM proved to be a poor way of financing the project, with many backers eventually withdrawing their support due to the team’s slow progress and lack of results. The team would eventually win the Constructors’ Championship but not until the early 1960s.

The 70-lap 1950 British Grand Prix began at 3pm and it was estimated in the programme that it would finish at 5:15pm – an almost exact estimate, given that Farina won the race in a time of two hours and 13 minutes!

The race was watched by fans from grandstands, or from behind ropes where the standing crowd was 10-deep in some places. Some others had placed platforms on top of their parked vans to get a better vantage point.

Royal Family in Attendance

At 2pm, the Royal Family arrived, with King George VI and Queen Elizabeth going on a tour of the circuit before taking up their positions in the Royal Stand. As a result of the royals attending – the first time a British monarch had attended a motor race – the event was billed as “Royal Silverstone”; a name which did not catch on. In fact, the 1950 British Grand Prix remains the only time that the reigning British monarch has attended a Formula 1 race.

At the time, the future Queen Elizabeth II was pregnant with daughter Anne. Contemporary photographs show Elizabeth’s sister Margaret – who bore a striking similarity to her sister – attending the event. It has led to some confusion that Elizabeth attended the event – but she did not. Her husband, the Duke of Edinburgh did, however, attend the Daily Express International Trophy, which was held at Silverstone later that year.

“The Race Goes On”

Motorsport was dangerous in the 1950s, but the race programme made it clear that “Whatever happens, the race shall go on”. The opening page features the words “motor racing is dangerous and persons attending at this track do so entirely at their own risk” – words which remain present in one form or another on tickets for motorsport events across the world to this day.

Later on in the race guide, a notice appears to remind fans of why certain signs are in place. It warns fans – who were unprotected by catch fencing and usually had little more than a rope preventing them from being struck by a wayward vehicle – that signs are put in place to protect the safety of “men, women and children” and the drivers, as well as for everyone’s convenience.

The programme makes the assertion that motorsport “must have its dangers”. The safety-second attitude towards motorsport in the formative years of the World Championship is clear. Races really were never stopped, no matter what happened. No Formula 1 races were red-flagged until the 1971 Canadian Grand Prix, despite 13 drivers – and multiple spectators – being killed during Grands Prix over the 21-year period.

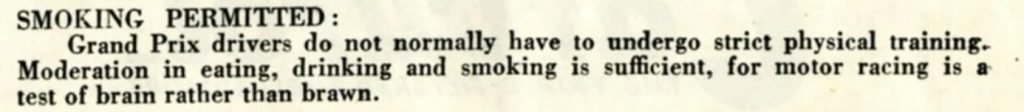

Another notable change in attitude is that of driver fitness: “Grand Prix drivers do not normally have to undergo strict physical training […] for motor racing is a test of brain rather than brawn.”

Silverstone Traffic Jams Are Nothing New

“Only by orderly behaviour and keeping to prescribed routes can speedy exit from the track be ensured. You don’t want a traffic jam, neither do we, so please don’t start one.” That’s the word of warning from officials in the race programme for the 1950 British Grand Prix.

There is no official attendance figure for the 1950 British Grand Prix – though there are estimates of a race day attendance of between 100,000 and 150,000, while some sources cite a figure as high as 200,000. By comparison, the 2023 British Grand Prix attracted a sold-out race day crowd of 152,000 (with a record-breaking four day total of 480,000).

Being rurally located, Silverstone has always struggled with traffic entering and leaving the circuit over race weekend. The current system in place in 2024 certainly helps things move quicker than in earlier days.

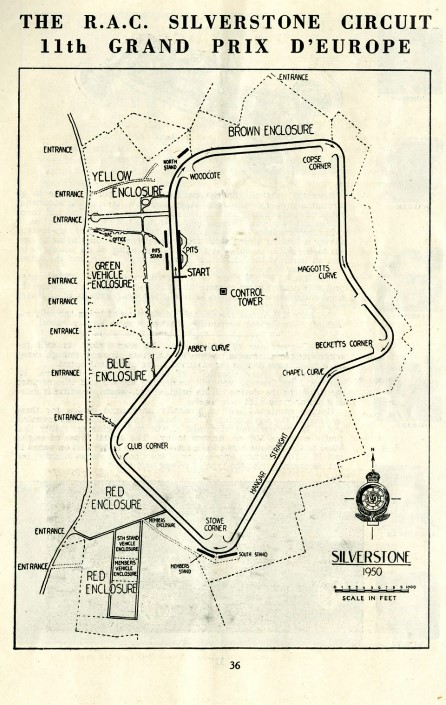

There was some effort to ease congestion at the 1950 British Grand Prix, with the circuit map showing different coloured zones for ticket holders to park their cars in. Fans reportedly began arriving and filing the car parks as early as 6am on race day.

Did organisers succeed in preventing traffic jams? Contemporary reports of a four and a half hour queue to leave the track after the race suggest not. Some fans’ arrival to the circuit on race day were also delayed due to similar problems. The Royal Family missed out on most of the traffic chaos, however, as they arrived by train at the now defunct Brackley station.